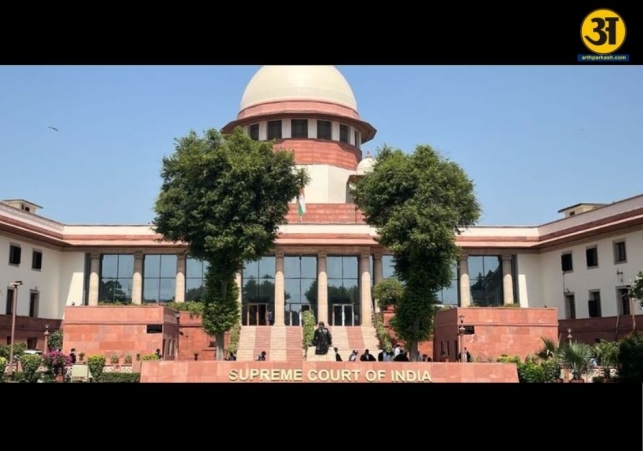

Verdict alters outlook on governor powers

Top court ruling reshapes political expectations in state governance debate

The recent Constitution Bench ruling of the Supreme Court has changed the political mood around the debate on the powers of state governors. For months, several opposition-backed commentators and activists had hoped that the court would impose strict limits on governors, especially in states ruled by non-BJP parties. They believed the judiciary would set fixed timelines for governors to approve or reject bills, introduce the concept of “deemed assent,” or firmly punish delays in decision-making.

These expectations grew louder because political tension between governors and state governments in places like Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Telangana had already created a strong public narrative. Many commentators projected the hearings as a historic moment where the judiciary would redefine the governor’s role. But the Supreme Court took a different direction—one based on constitutional principles rather than political expectations.

The Bench explained that Articles 200 and 201 of the Constitution were designed with flexibility. These provisions allow governors to return bills for reconsideration, grant assent or send them to the President. However, the Constitution does not give strict time limits for these actions. The court clarified that such timelines cannot be created by judges because it would amount to rewriting the Constitution. Similarly, the idea of “deemed assent” was ruled out because it would require the judiciary to take over the governor’s role, which goes against the principle of separation of powers.

This ruling exposed the gap between what many political voices expected and what the Constitution actually permits. It reminded everyone that judicial review has limits. Courts can act when there is extreme delay without explanation, but they cannot direct governors on how quickly decisions must be made.

Court reinforces constitutional boundaries

To understand the disappointment of some political observers, it is important to look at the earlier developments. A two-judge bench had previously criticised delays by the Tamil Nadu Governor and hinted at possible timelines. This led many to believe that the Supreme Court was preparing to take a strong stand. But that earlier ruling was not consistent with long-standing constitutional judgments, and legal experts had already suggested that it would not survive detailed examination by a larger bench.

The Constitution Bench returned to these older principles. It recalled judgments like Shamsher Singh, Hoechst Pharmaceuticals, Nabam Rebia, Bommai, and State of Rajasthan, which stress that governors hold a unique constitutional position. They generally act on the advice of the elected government but retain limited areas of discretion. The court repeated that this discretion cannot be eliminated by judicial orders unless there is evident misuse.

The court also highlighted Article 361, which protects governors from legal proceedings for actions taken in their official role. This further supports the idea that courts cannot supervise their daily functioning. The judiciary can only check whether the governor has abandoned constitutional duties altogether. But it cannot dictate the pace of constitutional decision-making.

ALSO READ: When heart trouble hides: Why major artery blockages often show no symptoms

ALSO READ: What happens if antibiotics stop working: the rising threat of superbugs

The ruling also clarified that a presidential reference under Article 143, which the President had initiated in this case, does not allow the court to act as a lawmaker. The Supreme Court can only interpret the Constitution—not create new rules or timelines. This point alone defeated the political expectation that the court would redesign how governors operate.

As a result, the Bench reaffirmed a balanced constitutional system. It said that the absence of deadlines in the Constitution was deliberate. The framers wanted to maintain space for dialogue between the state legislature, the governor and the Union government. That space cannot be closed by judicial intervention.

This judgment forces a rethinking of the public debate that surrounded the hearings. Some commentaries had portrayed governors as obstructing state governments and argued that the judiciary should step in aggressively. But the court made it clear that constitutional offices cannot be judged purely on the basis of political disagreements. Governors cannot act as partisan players, but courts cannot assume that role either.

The ruling is not a win for any political side. It simply restores the constitutional balance that has existed for decades. For the central government, it is confirmation that the governor’s position remains unchanged. For the opposition, it is a reminder that political expectations cannot override constitutional design. And for the judiciary, it reinforces its tradition of self-restraint.

The biggest setback is for those who shaped public opinion by suggesting that the court was preparing to limit gubernatorial authority. Their claims have now been corrected by the Constitution Bench’s clear reasoning.

The judgment also delivers an important lesson for democratic institutions. Governors must avoid turning discretion into obstruction. Courts must avoid turning review powers into tools for rewriting the Constitution. Legislatures must not use political conflict to demand judicial activism.

By refusing to impose timelines or accept the idea of deemed assent, the Supreme Court has protected the basic structure of separation of powers. It has shown that constitutional design cannot be changed to suit political convenience. The ruling reminds everyone that constitutional boundaries protect democracy—and that each institution strengthens itself by respecting its limits.